Last week was very interesting and eventful for those of us interested in issues of race and criminal justice. On Tuesday I attended the parliamentary launch of new research on joint enterprise legislation which received broad cross-party support for its findings. Then on Sunday the Prime Minster announced that David Lammy MP has been asked to lead a review of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) representation in the Criminal Justice System (CJS), and to investigate evidence of possible bias against black defendants and other ethnic minorities.

The review

In announcing the review the Prime Minister said that we need to ask difficult questions about whether the system treats people differently based on race. The review will scrutinise charges, courts, prisons and rehabilitation and report in Spring 2017.

This announcement follows over two years of work by Clinks and BTEG to support the Young Review into improving outcomes for young Black and Muslim men in the CJS, chaired by Baroness Young of Hornsey.

A couple of years ago when Clinks, BTEG and Baroness Young embarked on the Young Review it felt as though issues of race and the CJS couldn’t have been further down the political agenda. We therefore welcome this review and believe it is testament to the hard work of everyone involved in the Young Review and others who have worked tirelessly on this agenda over past decades.

New research shows how a 300 year old duelling law is sweeping BAME people into our prisons

This review announcement comes in the same week as a new report was launched showing how joint enterprise legislation and the use of gangs in policing and prosecution is, according to Stephen Pound MP at the parliamentary launch of the research, “sweeping up young Black and minority ethnic young people into our prison system”.

Swordsmen duelling at dawn is probably not a familiar image for most young people today. However, the joint enterprise legislation introduced 300 years ago to discourage it means that an individual can be convicted of a crime if they are present when that crime is committed, or for being with those persons who commit the crime and not trying to stop them. Even if an individual is not present at the crime scene they can be found guilty of the main offence if they had the foresight that it might happen.

In modern times this law has been rarely used, until the last ten years or so when it has been increasingly employed in response to serious crimes, usually murder, and often where these crimes are believed to be connected to gang activity.

Research by Patrick Williams and Becky Clarke at Manchester Metropolitan University, published by the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies, draws on a survey capturing the experiences of 241 serving prisoners, convicted under the joint enterprise legislation, and explores their experiences and the relationship between the use of joint enterprise and evidence of gang involvement in the prosecution process.

The research has three key findings which illustrate how joint enterprise and the use of gangs in policing and prosecution strategies is leading to the disproportionate criminalisation of BAME young people and contributing to the disproportionate number of BAME people in our Criminal Justice System.

It finds that prosecutors regularly rely on racial stereotypes in relation to Black joint enterprise defendants in order to create association between the individual and the event and to establish foresight. For, example prosecution teams were reported as being more likely to use gang insignia and music videos or lyrics, particularly ‘hip hop’ and ‘rap’ genres, as a way of building a joint enterprise case against BAME prisoners.

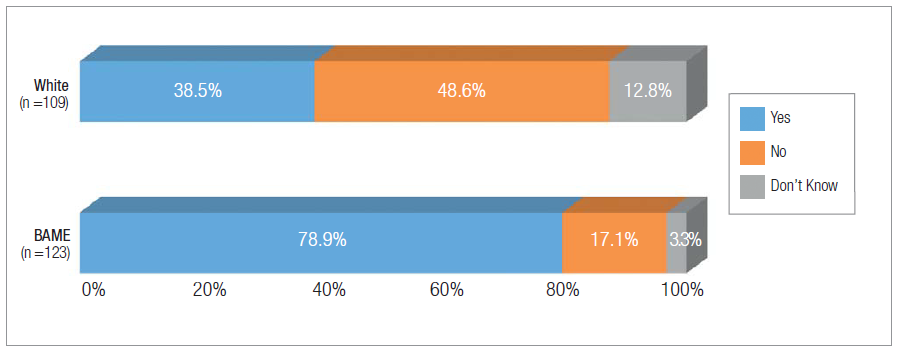

Gang associations were more likely to be cited in the prosecution of BAME joint enterprise defendants than white defendants. However, the overwhelming majority of individuals contested that their associations with their co-defendants reflect ‘gang’ involvement and were more likely to describe them as family or friendship ties.

(above) Joint Enterprise prisoners reporting the prosecution making reference to gang membership at trial, by ethnicity

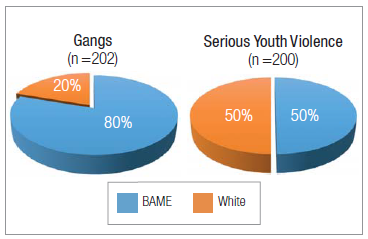

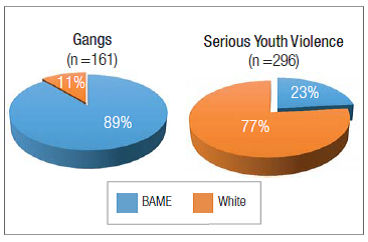

The research found a concerning disconnect between gang registers and serious youth violence. Drawing on data from criminal justice sources in Manchester, London and Nottingham, the research highlights differences in the profile of those identified as ‘gang involved’ and those convicted of serious youth violence. In all three cities the gang construct is racialised to BAME men. BAME young men are overwhelmingly identified and registered on ‘gangs’ lists but do not appear to be responsible for the most serious violence, with official data showing that most convictions for serious youth violence are of white people.

(above) Gang and serious youth violence cohorts, by ethnicity, for the London area

As well as these findings the research also raises important questions about the impact of racialised gang discourses on the unequal outcomes experienced by BAME people in prison and on release, and how such labels follow an individual through their criminal justice journey and beyond. For instance in prison, individuals can face challenges to engaging in rehabilitative programmes and interventions if they question the legitimacy of their conviction. On release, gang involvement can have a significant impact on the conditions of an individual’s probation including restrictions on the type of employment they can undertake, the area they live in, access to children or association with other family members.

on the unequal outcomes experienced by BAME people in prison and on release, and how such labels follow an individual through their criminal justice journey and beyond. For instance in prison, individuals can face challenges to engaging in rehabilitative programmes and interventions if they question the legitimacy of their conviction. On release, gang involvement can have a significant impact on the conditions of an individual’s probation including restrictions on the type of employment they can undertake, the area they live in, access to children or association with other family members.

(above) Gang and serious youth violence cohorts, by ethnicity, for the Manchester area

Ensuring David Lammy’s review builds on previous work to adequately tackle racial bias

This joint enterprise research makes a hugely important contribution to the body of evidence relating to race and the Criminal Justice System and the causes of the disproportionate number of BAME people at every stage of it. Similarly, the Young Review made a series of recommendations in December 2014 regarding improving outcomes for young Black and Muslim men in prison and on release. It’s vital that David Lammy’s review builds on these findings and recommendations as well as those of other groups working on issues of racial disproportionality in the CJS, such as Stopwatch.

The review is an opportunity to consider racial bias across the whole of the Criminal Justice System; from arrest to resettlement. Clinks, as part of the Young Review steering group will work to support David Lammy's review and to ensure that it is fully engaged with the findings and recommendations of the Young Review and others working in this area.

What's new

Blogs

GUEST BLOG: #Clinks26 - Understanding the Impact of Lived Experience at My First Clinks Conference

Publications

Latest on X

The role is for a leader from an organisation focused on racially minoritised people, with expertise in service delivery, policy, advocacy, or related areas in criminal justice. Racial disparities are present at every CJS stage. This role ensures these voices are central in shaping policy to help address and eradicate them. Apply by Mon 18 Nov, 10am. More info: https://www.clinks.org/voluntary-community-sector/vacancies/15566 #CriminalJustice #RR3 #RacialEquity